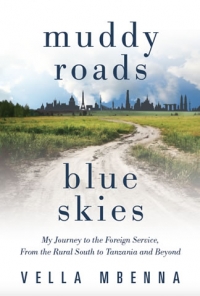

Muddy Roads Blue Skies

Chapter 4: Resilience, Excerpt

After the US Embassy in Tanzania was bombed in August 1998, I remember the paralyzing effect it had on some of my colleagues. Sitting in the van to go from the bombed embassy to our safe haven, I saw the traumatized faces of people clenching their seats and holding each other or a wounded area of their body. When we arrived at the safe haven, they huddled inside the house, stunned, some unable to contribute, even though I know they wanted to. I understood their fear. I, too, was shaken by the disaster. Had I stopped to think about the effects of what had just happened, I might not have made it through that day without breaking down. Looking back, I believe I kept my composure by concentrating on getting needed equipment out of the embassy and reestablishing communications.

Yet weeks later, when the reality of a new normal had set in for most of us, it was obvious that what had happened had a deep effect on us all. Folks were just not the same. Some who I thought were slackers had stepped up to the plate and were working like crazy. Some who you would think would be resilient and hard-charging after such a horrific event seemed to have retracted into themselves and sometimes had to be told step-by-step what to do. It was like I had to learn how to work with a new team amid chaos. It was quite an experience, because I was new, too. I never knew I could stand tall through such an unimaginable thing. When I saw others breaking down, I stopped and consoled them, thinking deep down, Why this person and not me?

It was only then that I recognized an internal trait that had gotten me through many of the hard times in my life. Momma called it “get up and get it done!” Friends said I was not thinking straight because, for days after the blast, I kept going into a bombed embassy that was not structurally sound to bring things out to ensure colleagues could resume work with familiar and necessary items. I did not pity myself or think of my personal safety. When I got up off the floor in my communications center the day of the bombing, I dusted myself off and got things done— just like Momma taught me. I never stopped unless I was sleeping, and I did not do much of that.

A few of my colleagues accused me of being stoic, since I did not linger in what had happened. I laughed when I heard such comments because they were far from the truth; I was thinking straight and cared deeply for all who were killed or sustained injuries. I was resilient. And, my goodness, there was more work to do than ever—and with a smaller staff. I stepped up to the plate and worked above and beyond what was expected of me because it was my duty and because of what was instilled in me—resilience. I joined the Foreign Service to face challenges, and this was the roughest in my career to date.

Of all the traits needed to survive in the Foreign Service, resilience is probably one of the most important. Every two to four years, your life turns topsy-turvy. A new job, country, friends, colleagues, phone number, food, lifestyle, climate, house—everything changes.

After a hard day at work, when all you want to do is curl up on the couch and watch your favorite television show, you can’t, because television programming changes from country to country. You might not even have your favorite coffee mug or throw, as your household effects take months to arrive from your last post. Even after your pots and pans arrive, it’s not like you can cook yourself some comfort food. Try shopping for grits in Beirut or guacamole in Kinshasa.

Resilience means pressing on or over obstacles. All that bad crap that went down with my first two marriages? There’s no way I could have embraced the possibilities presented by the Foreign Service if I’d had my arms crossed and fists clenched. No sulking or burying your head in the sand. No pity parties. Make amends. Forgive. Be flexible. Move on. Resilience never looks back.